By now we know well that everything changes. And still, after the mind-blowing ascents of recent Patagonia climbing seasons, I feel like we’re witnessing something special, almost like seeing leaps into the future in present tense. Perhaps I’m overstating things. Time will tell.

When researching for my book, and reflecting on history through the lens of today, I was frequently struck by the futility of predicting the future. Here is one example, from an editor’s note in the 1959 AAJ after they received word of the supposed Egger-Maestri climb:

Armed with today’s perspective, I shouldn’t be surprised at the phenomenal recent ascents. I am, however, awed. Regardless, and with full respect to the current rate of progression and the next-level skills of today’s top climbers, I think it’s fair to say that the single biggest change in the history of Patagonian climbing occurred far from the mountains, circa 2005.

Below is an article I’ve been meaning to post for some time. It’s similar to a piece I originally wrote for the 2014 Alpine Journal (U.K.), and is mostly a stitched-together excerpt of my chapters 17 (New Patagonia) and 24 (Demystification of a Massif). It’s about that massive change I just mentioned – the delineation between Old Patagonia and New Patagonia, and the story of how it happened.

***

New Patagonia: The Winds of Change

Imagine yourself weary and worn, camped in the woods of Patagonia, just back from an attempt where a sucker-window of weather had slammed shut as you were three thousand feet up your climb. It was as if the fury of the gods had suddenly descended upon you, but somehow you’d survived. Your body went numb, the wind slammed you into the wall, and you couldn’t hear your partner yelling at you from three feet away. Every second of every hour for the next twelve was laced with a primal fear. Then, you staggered back to camp and crashed out, deep into a dreamless sleep. You hadn’t slept in thirty-some hours and as the storm raged, you hoped for only one thing: that it would continue, so you wouldn’t even have to think about going back out there. But in the middle of the night you had to piss. You’d rolled over and mumbled, unzipped the tent door, and staggered outside. Through bleary eyes your gaze strayed to the gaps between the lenga trees, and you’d seen stars shining bright. Fuck.

In 1975, following one of his many Patagonian expeditions, Ben Campbell-Kelly wrote: “An expedition should be prepared to be spending a minimum of three months in the mountains, particularly if they have chosen a difficult objective.”

A Polish team racing the wind and incoming storm high on the Compressor Route in 1996 (Gregory Crouch photo).

In 1995 on Infinito Sud, an incredibly difficult new route up the center of Cerro Torre’s south face, Italians Ermanno Salvaterra, Roberto Manni, and Piergiorgio Vidi hauled a 200kg aluminum box for shelter as they went, to wait-out storms. Salvaterra, Cerro Torre’s all-time greatest climber, had been worried that regular portaledges would be destroyed by the wind.

In his 2000 book, The Big Walls, Reinhold Messner wrote: “The big problem on Cerro Torre is the storms. Every big face there should really be measured twice.”

But that was then. Old Patagonia. Before the arrival of the single biggest change in the history of Patagonian climbing, which wasn’t the bridge over the Río Fitz Roy, or the airport in El Calafate, or the paved roads, or even the evolution of modern climbing gear.

—

This change affected every element of Patagonian alpinism, even – or perhaps most of all – the attention paid to the area’s most infamous and bizarre route: The Compressor Route, on Cerro Torre. Over the course of two trips in 1970 (often misreported as 1971), Italian climber Cesare Maestri used a gasoline-powered air compressor to jackhammer some four hundred bolts, most of them spaced to be used as ladders, into the mountain’s southeast ridge. Maestri placed many of his bolts beside perfectly usable cracks, while elsewhere he launched up blank stone, seemingly determined to avoid natural features.

Though Maestri returned home to terrific fanfare, the greater climbing world was less impressed. Most climbers considered his tactics an affront to the spirit of alpinism and to long-held notions of fair play.

But in the ensuing decades, something curious happened: The Compressor Route became the most popular route on Cerro Torre.

Few climbers even attempted other routes on the mountain. Until the mid-2000s the Ragni Route, the next most popular route and Cerro Torre’s line of first ascent, was summited only four times.

Even as more climbers came and tried, multiple years would pass, often consecutively, without Cerro Torre seeing a single ascent. Each summit-less season, each nightmarish attempt that ended in a hellacious storm, and each rare success further embedded the Compressor Route as part of Cerro Torre’s lore. For many climbers, the moral affront of Maestri’s prolific bolt ladders became easier to overlook.

Tales of terror were omnipresent. Since storms race in from the west, if you were high on the Compressor Route, you wouldn’t know you were in trouble until it was too late. Eyelids froze shut. The wind would send ropes sailing horizontally into space before shifting and launching them back into the wall like wild, slithering snakes, twisting them irretrievably around flakes and forcing climbers to cut their ropes and make ever shorter rappels with what remained. Climbers would stagger down to the safety of the forest looking like battle-worn soldiers, their eyes fixed in thousand-yard stares.

In 1980 Kiwi climber Bill Denz made thirteen attempts to solo the route. He endured a seven-day bivouac trapped on a tiny ledge a thousand feet below the top on one attempt. Another time, his best attempt, Denz retreated only two hundred feet below the summit.

Each previous suitor validated the next, particularly when many were renowned figures – starting with Jim Bridwell’s 1979 true first ascent of the route (Maestri, it was later learned, retreated from below the top in 1970), which effectively bestowed the blessing of climbing royalty.

Mauro Giovanazzi attempting a new route on the east face of Cerro Torre in 2001 (Ermanno Salvaterra photo).

As testament to Cerro Torre’s inherent difficulty, aside from the four complete ascents of the Ragni Route, until 2005 every other climb to the summit depended upon using the bolts of the Compressor Route to get there. The three routes on the south face descended upon intersecting the southeast ridge, while the two routes on the east face finished to the summit via the Compressor Route.

By the time a nearly two-week-long stretch of clear skies hit the Chaltén Massif in late November and December 2008, the number of Compressor Route ascents had grown too many to count, but stood at well over one hundred.

That late 2008 weather window, however, was different. Not only because of its duration, but because everybody knew it was coming.

In his Chaltén Massif summary in the American Alpine Journal, Rolando Garibotti wrote: “The big news was that the Ragni di Lecco Route on the west face of Cerro Torre had six ascents (nineteen climbers), more than all previous ascents of the route combined. In contrast, the season saw only one ascent of the Compressor Route. It is as if overnight everyone stopped climbing Everest with oxygen, fixed rope, and Sherpa support. While Maestri’s hundreds of bolts remain in place, the climbing community appears to have finally given them a cold shoulder. The list of non-Compressor Route ascents of Cerro Torre has now grown to fourteen.”

—

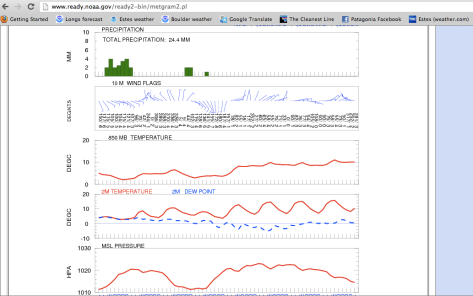

Weather balloons had probably been going up around Patagonia long before anyone made forecasts, Jim Woodmencey told me. He’s a climber, skier, and former Grand Teton National Park ranger who owns a forecasting company called MountainWeather. He says each country has weather service stations, and they launch balloons that gather data at various points in the atmosphere. There are other ways to gather data as well, like surface observation stations, ocean buoys, and satellite photos of clouds at different elevations and time intervals, which indicate things like wind speed and atmospheric moisture concentration. Even though data is comparatively sparse in less-populated places like Patagonia, virtually nothing stands between the storms brewing in the Pacific Ocean and the Chaltén Massif. Thus, unlike many prominent alpine destinations, the data collected allows for incredibly precise forecasts.

Data alone means nothing, though. It’s computer models that actually analyze the data and make predictions – forecasts – and they’ve improved tremendously over the years. Data transformed into a forecast answers the key question: Is it climbing weather, or not?

In the 2004–05 season, German climber Thomas Hüber decided to see if his weather guru, Karl Gabl, could provide forecasts from afar. Forecasts for the Chaltén Massif were unprecedented. “We had no idea if it would work for Patagonia,” Thomas told me. “But it worked, so everybody was looking at me to see if I’d go or stay, because the climbers thought I knew via Innsbruck the secret about the weather. I had a great first season. Not only for Patagonia but everywhere, weather reports changed a lot in alpinism.”

As Gabl’s forecasts have shown over time, accurate mountain forecasts require specific knowledge. Even if you could teach yourself how to do it, you’d need the ability to access the information, which requires functional Internet access.

The Internet didn’t come to El Chaltén until 2003. Even then, it was scarce, and it barely worked. The first locutorio (Internet cafe) arrived in 2004; climbers would come to check the weather on NOAA, but they’d struggle because the connection was so bad.

Local resident Adriana Estol recalls, “I came here in 2006 and it was almost impossible to have Internet at the house, but some houses were lucky.” One of the lucky houses belonged to Bean Bowers.

Bowers, a tough-as-nails alpinist and full-on lifestyle climber from the U.S., was always the do-it-yourself sort. For several consecutive years, he’d lived the entire season in El Chaltén, and he’d scraped together enough money to buy a small house there. In 2011, at age thirty-eight, Bean died of cancer, but several of his friends remember how he figured out the weather. He guided in the Tetons in the summers, where, one season, Climbing Ranger Ron Johnson showed him how to read weather models. Bowers then took a course from Woodmencey on mountain weather forecasting.

Doug Chabot, an accomplished alpinist and avalanche forecaster, also helped out. “I gave Bean the weather basics on forecasting in 2004 since he was keen to learn. In fact, during his first trip there [to El Chaltén], he would call me to check on a few weather models. I was avalanche forecasting; I’m used to looking at weather models every day.” He added, “Most importantly, I had a real job and was reachable by phone.”

Climber Josh Wharton remembers well the first season of forecasts, as he and the late Jonny Copp were climbing together in the massif. Many climbers expressed gratitude to Hüber for sharing his forecasts that season, and soon the gratitude would shift to Bowers. “Bean was reading the navy maps a friend had showed him, but he was still pretty new to it, so it wasn’t always that spot-on. Thomas Hüber was using a satellite phone to call his Austrian meteorologist, and between the two I remember growing increasingly confident throughout the trip. In fact, when Jonny and I started down Poincenot [the final tower in their fifty-two-hour linkup of Agujas Saint-Exupéry, Rafael, and Poincenot], the wind came up harshly right on queue, almost to the hour Thomas’s guy had predicted three days earlier. It was an ‘ah-ha!’ moment!”

As he was learning, Bowers kept his dirtbag forecasting knowledge close to his chest, mostly sharing it with friends. In 2006 he taught it to Rolando Garibotti, and soon climbers were knocking on their doors asking for forecasts and how-to instructions. After all, knowing the weather in Patagonia was like having a golden ticket – and it was especially good because it was free.

Climbers literally lined up at Garibotti’s house wanting to learn, so he typed up a how-to email (now he has a weather forecasting section on his pataclimb.com website). Before long, everyone could get a spot forecast for the massif. Just follow the steps, punch in the data on the right websites – the location coordinates for Cerro Torre, by the way, are -49.3° and -73.1° – and you get frighteningly accurate projections for precipitation, temperature, and, most importantly, wind speed.

It was as if the walls shrunk.

—

Left: El Chaltén in January 1986, less than one year old, with the red roof of the town’s only building faintly visible (Sebastián Letemendia photo). Right: El Chaltén, January 2013 (KC).

Within a few years of that 2004–05 season, the forecasts had become so accurate that climbers could confidently leave behind most of the storm gear they used to carry, making for lighter loads and faster climbing. Around the same time, interest in the Compressor Route rapidly subsided. Maybe it took the clarity of blue skies to bring to the fore what most climbers objectively knew: The Compressor Route was so compromised that it was hard to consider it a valid climbing route. Detractors of the route had long argued that having the entirety of difficult climbing covered in bolt ladders removed too much of climbing’s innate natural challenge. When doing it in perfect weather, they were right.

Yet it’s an interesting interaction, because weather and conditions are integral to alpine climbing. Climbing the Compressor Route in Old Patagonia meant something different than getting up it in New Patagonia. Remove the crippling fear of being caught in one of those legendary storms, and the change in Patagonian climbing is impossible to overstate.

Nowadays in El Chaltén (nobody camps in the woods anymore), between bouldering sessions climbers can be heard saying things like, “Yeah, looks like sixes and eights tomorrow, then dropping to twos on Wednesday.” They are talking knots of wind speed at the lower, forecast elevation, which translates into nay or yay for climbing at the higher mountain elevations.

In early 2007, I remember staring over Bean Bowers’s shoulder as he pulled up the weather map on his computer: The mother of all high-pressure systems was coming our way. The skies were clearing from there to Australia for four days, and so Colin Haley and I headed for Cerro Torre, where we completed an oft-attempted link up of François Marsigny and Andy Parkin’s 1994 route Los Tiempos Perdidos to the summit via the Ragni Route. Despite the exposure to the ice cap, and the harrowing story of Marsigny and Parkin’s epic retreat from high on the route, Colin and I climbed with ten-pound backpacks. Our only concern was whether or not we could climb the route; we didn’t worry about storms (someday a forecast will be deadly wrong and trap climbers like us). While it was one of the best climbs of my life, I also realize that we were playing an entirely different game than the climbers of Old Patagonia.

I was again struck by the difference, the evolution, when I visited El Chaltén in 2013. A friend had been monitoring the forecasts from the U.S. and saw a window coming. He took advantage of today’s increased accessibility, hopped a plane and a few days later climbed the Ragni Route. Around the same time, a pair of strong young Slovenians arrived, dropped their bags at their hostel – the forecast was perfect – and, without sleep, ran up the trail to Fitz Roy and established a hard new route. Afterward, in town over dinner and at the bars, while storm clouds thundered through the peaks, in comfort we all swapped stories of our ascents.

Practically overnight, climbers could avoid the most horrifying and brutal component of Patagonia climbing while resting and bouldering in the shadow of the mountains, ready to strike when the weather clears.

The place would never be the same.

Something relatively new this year has been how consistently the forecasts have messed up wind forecasting, though. Over the past three weeks that we have been in town, I’d say the forecast was dead wrong 5 or 6 times with Patagonian winds when it should have been nice and quiet. This seems to correlate with a breakdown of the weather models, and we are seeing the same in Chamonix, with even very short term forecasts gone completely wrong much more than a few years ago. It will be very interesting to see if weather scientists can adjust the models or if a degree of uncertainty will be added back in the mix in seasons to come.

Hi Alex, it is not a breakdown in the weather models. The models are working as well as always, it is just the NOAA meteogram that shows the wind wrong. If you look at the Patagonia Vertical facebook page we posted something about this about two months ago. The way to circumvent this issue is to look at the wind in the NOAA windgram, where the wind speed is show correcly. There is no issue with the GFS model, or with the NAVGEM or ECMWF models, they all show the wind accurately. The problem only occurs in the NOAA meteogram, we assume it is a glitch on the software, when in retreives the info from the GFS database. Any questions let me know, Cheers Rolo

Kelly,

Being an atmospheric scientist who has worked in mountain weather prediction for most of my career (and a friend of Jim Woodmency’s), I really enjoyed this article. I don’t think I’ve ever ready anything that summarizes so well the tremendous impact of recent weather forecasting advances (and there are more coming). Great writing. I’ll be picking up a copy of your book ASAP.

Jim Steenburgh

Professor of Atmospheric Sciences

University of Utah

Wow, so cool to read your comment, Jim. Thank you!

Fantastic piece. Thanks for publishing it. I remember chatting with you about this, but as always, the words shine when you write ’em down!

Kelly – Just wanted to compliment you on an exceptional post. You found a way transform a bunch of incremental technical details of what changed Patagonian climbing into a cohesive story. Your depth of personal experience, background knowledge, and command of the issues is obvious. Just excellent journalism – thanks for taking the time and hard work to put this together!

A bit late to this, but the next gen kids will maybe think to climb this stuff “clean”, so to speak, without the advantage of pulling up on a digital sling. But meanwhile, those who did suffer in the Old will bask in the New freedom, right?