I’m awestruck by the stories of Old Patagonia. You can read them in the AAJ and other climbing periodicals, maybe hear some ‘round campfires, and you can find others in books – one of my favorites is Enduring Patagonia, by Gregory Crouch. I encountered scores of these stories during my Patagonia research; my selected bibliography contains 256 references (many more informed my thinking), and I conducted in-person interviews in seven different countries.

Yet sometimes you’re taken by something as simple as a hastily-snapped photo. This, for me, is one such picture:

Photo © Silvo Karo

The photo belongs to the great Slovenian climber Silvo Karo, and he’s allowed me to post it here. On the left is Francek Knez, on the right is Stane Klemenc. The year was 1983, and they’re establishing a difficult and dangerous new route on Fitz Roy, which they called Hudičeva Zajeda (Devil’s Dihedral).

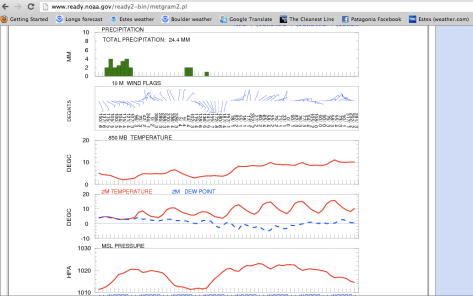

Take a moment. Study the hardware, the wool mittens, the fur-lined parkas. The atrocious conditions. The expression on Knez’s face, and the snow-filled helmet that he isn’t bothering to wear. Think, 1983 – no sat phone, no helicopters, no rescue crew. The town of El Chaltén didn’t even exist at the time. Much less weather forecasts. Which, as you can deduct from my last post, New Patagonia, is why they’re stuck climbing in a storm.

It isn’t that bad weather no longer happens in Patagonia – it does, and several deaths in recent seasons were related to exposure after things went wrong on a route. Rather, if all goes right, you now have the means to avoid the storms. Rolando Garibotti, the undisputed climbing expert of the area, told me, “Before, any day with any clouds was not a climbable day. We would all wait for the splitter weather, at least to start up on climbs. These days any day with lower winds is a climbable day, even if there are clouds and humidity in the air.”

One of the most astounding outings from the 2014–15 season points to how top climbers can thread the needle like never before. Here’s Rolo, discussing Colin Haley and Alex Honnold’s initial attempt at a one-day ascent of the Torre Traverse (they succeeded in 2016): “On day one it rained until 5 a.m., they started climbing anyways, knowing it would improve, they got to near the summit of Cerro Torre by 3 a.m., in 22 hrs, but the weather shut them down. Wind that was supposed to arrive at noon arrived early. This was a 20-hour window. Before forecasts, you would not have even done the approach.”

But to the historically bad weather: Has it improved in recent years?

Seems like it. But while anecdotes and uncontrolled observations suggest longer weather windows since the mid-2000s, I’m hesitant to jump to conclusions. Stories can be invaluable in shaping our understanding of different times, people, belief, and a number of things I dealt with in my book. But with this, stories aren’t enough. I want evidence.

Consider, for instance, that within the last decade exponentially more climbers have visited the Chaltén Massif, many staying the entire season. They rely on an infrastructure in town that did not previously exist, and are ready to strike at even the narrowest weather windows – even climbing in cloudy weather, so long as the winds are low and the clouds aren’t storm clouds. And then, with the advent of social media, any alpine activity today is infinitely more visible to the outside world. All of these things influence our perceptions.

Furthermore, despite our suspicions of better weather likewise arriving in the last decade, it’s important to remember that it surely isn’t black and white. Meaning, if the weather has improved, it probably didn’t jump from Old Patagonia to Palm Beach.

We shouldn’t mistake anecdotes for objective truth. Even if such assumptions prove correct from time to time, as a rule it’s a lazy way to think, one laden with traps. You don’t want to drift toward the mouthbreathers who dismiss the expert consensus on global warming because it got cold that one weekend last June. Even if it did fuck up your NASCAR lawn party.

The problem with Patagonian weather is that, far as any of us know, we don’t have good comparative data. Rolando Garibotti might be getting close, though. Rolo has some data summaries from 1977–2002 for Punta Arenas, the nearest longstanding weather station south of El Chaltén. The two places likely receive similar weather. And he rounded up some raw data from 2002–14, though they might not be comparable and we don’t know how to process it. Any weather experts out there?

Anyway, I’m getting a little off track. That photo of Silvo Karo’s, and Old vs. New Patagonia.

During my research, one evening at Silvo’s house in Slovenia our conversation drifted into an entire era. That era included the pinnacle years of Slovenian alpinism, of which Silvo was an integral player. Soon I barely spoke, just listening, completely rapt, as if I had a seat beside Moses as he recounted stories from the days of the tablets.

***

Here’s the part about Patagonia, an expanded excerpt from Chapter 24:

Silvo Karo has climbed in both Old and New Patagonia. He endured vicious days while establishing difficult and dangerous new routes on the east face of Fitz Roy in 1983, the east face of Cerro Torre in 1986, and the south face of Cerro Torre in 1988; all three routes are unrepeated. By the time of his January 2005 trip, Internet weather forecasts had just arrived. He and fellow Slovene Andrej Grmovšek started at the base of a connecting formation three thousand feet of technical climbing below Cerro Torre and raced up to the Compressor Route, which they took to the summit. It was as if they were in a playground. Their linkup became known as the Slovene Sit-Start, a half-joking reference to the world of bouldering, where the emphasis is on pure difficulty on small rocks, and climbers often start seated in the dirt and pull onto the first holds.

One night at Karo’s place in Osp, Slovenia, fall 2012, we were talking after dinner and a day of cragging. I asked about the old days in Patagonia. Karo’s hulking shoulders were slouched over his plate and wine glass, and then he leaned back to talk. He’s built like a linebacker but climbs with ballerina grace. He recounted the late ’80s and early ’90s, when Slovenian alpinists—this tiny country, then a part of Yugoslavia—set standards in commitment and difficulty that have yet to be eclipsed. Karo was a core part of the crew. It came at a cost; a staggering proportion of his friends and partners died in the mountains.

One night at Karo’s place in Osp, Slovenia, fall 2012, we were talking after dinner and a day of cragging. I asked about the old days in Patagonia. Karo’s hulking shoulders were slouched over his plate and wine glass, and then he leaned back to talk. He’s built like a linebacker but climbs with ballerina grace. He recounted the late ’80s and early ’90s, when Slovenian alpinists—this tiny country, then a part of Yugoslavia—set standards in commitment and difficulty that have yet to be eclipsed. Karo was a core part of the crew. It came at a cost; a staggering proportion of his friends and partners died in the mountains.

He said, “I think the thing that has changed a lot in Patagonia, the weather forecast, no? In 2005 was the first weather forecast, or one year earlier. I remember at that time, we were all down—it was so nice, the weather forecast, uff. You could just go and climb. Before? Nobody know.

“I remember, Jay Smith. He was also in Patagonia a couple of times [Smith established several new routes in Patagonia, including the first ascent of Cerro Standhardt in 1988], and one time he decide, OK, now I will start to write the details. All that change in the sky, I will just mark it. And maybe for one month he write the details: wiiiiindy from this side…clouds come from this side today, and tomorrow it is like this weather and then barometric pressure, he follow pressure and everything. But finally he didn’t find any signs to tell him, ‘OK, this-means-that-weather-will-be-good.’ Zero. And he decide, no, not possible. Not possible. Even local people living in town don’t know. But then, satellite and all these things…very precise, and then in advance they tell you.

“I remember last time in Patagonia, they have a weather forecast that will be: tomorrow start period of good weather for three days. And man, it’s just perfect. You just go to the wall at night, no problem, you sleep well, no shaking all the time with the weather, ooooooooh, it start snoooowing.” For a second his eyes drifted, like he was back on a tiny bivy ledge thousands of feet up when a storm arrived. Then he gently returned and smiled. “It’s tooootally different, no? Now to climb big climb in Patagonia it’s much, much, much more easier. And you don’t need to take anything just in case for protection, extra things, extra food. You know that next three days the weather will be good, and you will do it.”

I suggested that maybe something has been lost.

“Other things is gained, of course. You need to go with the time,” he said with a lighthearted laugh.

I agreed, while thinking of how everything changes and the future builds on the past. I mentioned that we still can appreciate the stories of old.

He nodded his head and started to speak. Then he paused, stared into an invisible distance, and didn’t say a word.